Drawing the Line on Gerrymandering

Throughout most of the U.S., maps for federal and state legislative districts are drawn by state lawmakers. A longstanding complaint about this procedure is that the politicians in office during the redistricting process frequently engage in “gerrymandering,” or drawing maps that help themselves and their political allies retain seats or gain additional power. Given that different areas of a state can have very different demographic and political makeups, drawing district lines in different ways can lead to large variations in who is ultimately elected to office [1]. In particular, partisan mapmakers can use two strategies to benefit their party. One is “packing,” where partisans try to put as many supporters of an opposing party as possible into a small number of districts in order to reduce that party’s influence in surrounding districts. The second, “cracking,” occurs when mapmakers divide supporters of an opposing party across as many districts as possible, in an attempt to prevent them from having a sufficiently large foothold in any one of these districts.

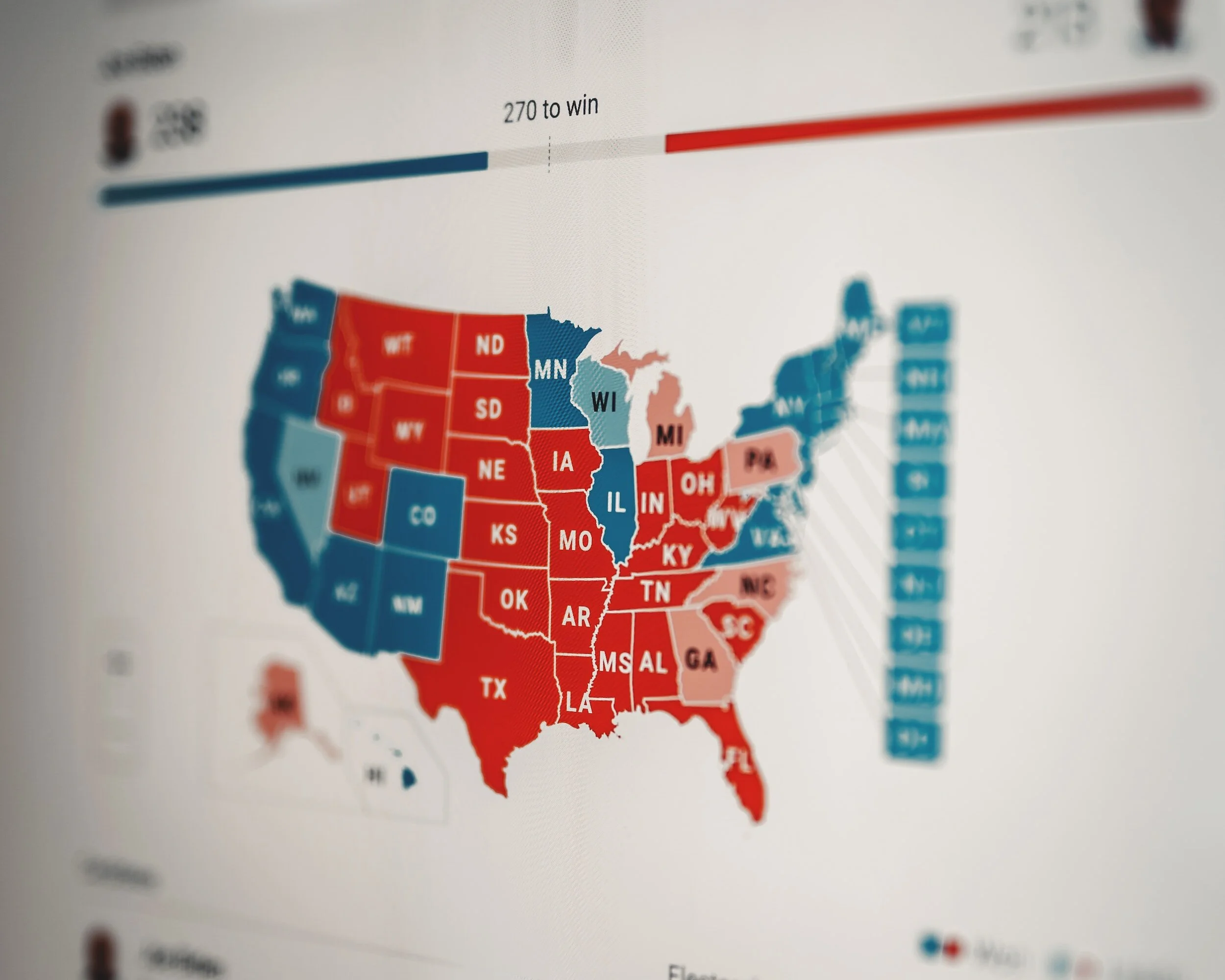

While both strategies have been commonly used in the past, the rise of big data and sophisticated electoral models have made them powerful tools for establishing a large political advantage. For example, in 2016 Republican congressional candidates in North Carolina received only 54% of the votes statewide but won 10 out of 13 House seats (77%) [2]. That same year, Republican candidates in Maryland received 37% of the statewide vote but won only 1 of 8 seats (13%) [3], and Democratic candidates in Pennsylvania won only 5 of 18 districts (28%) while receiving about as many votes statewide as Republican candidates [4].

The primary criticism of partisan gerrymandering is that it is undemocratic. If one party has an electoral advantage that far outstrips its popular support, this diminishes the power of the populace as a whole to enact its political preferences. Moreover, critics argue, intentionally diluting the political influence of some voters seems to violate the democratic ideal that all citizens should have equal voice. Relatedly, partisan gerrymandering might make citizens less politically engaged by making them feel like their votes won’t make any difference. Finally, critics often point out that partisan gerrymandering increases political polarization and undermines political cooperation; districts that are drawn to be “safe” wins for one party or another are more likely to elect extreme candidates than are highly competitive districts, which may favor more moderate candidates.

Yet not everyone views these maps as morally problematic. For instance, some argue that critics underestimate the force of larger cultural and demographic trends in driving politically lopsided districts—for example, that Democratic-leaning populations have been increasingly concentrating themselves in small, densely populated geographic areas. Even though intentional partisan gerrymandering does occur, it is far less significant than it is often portrayed. Additionally, it might be argued, politicians are not doing anything wrong in using political considerations when drawing legislative maps. This is just a normal part of electoral politics. After all, if these lawmakers were rightfully elected, then it is within their rights to draw districts as they see fit. In fact, some elected officials defend this practice as necessary for faithfully representing their constituents—if an elected representative’s job is to promote the interests of their constituents, it is their responsibility to draw legislative maps that also promote those interests.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

What, morally speaking, are the potential costs of the high levels of student loan debt in the U.S.? What, morally speaking, are the potential costs and benefits of these proposals to forgive this debt?

Are these student loan forgiveness policies unfair to people who do not currently have this type of debt? Why or why not

Should access to higher education be guaranteed to all? Should it be free?

References

[1] Wikipedia, “Gerrymandering”

[2] The New York Times, “North Carolina Districts Court”

[3] The Washington Post, “How Maryland districts pulled off their aggressive gerrymander”

[4] The New York Times, “Pennsylvania Congressional District Map Is Ruled Unconstitutional”